Published on

Tuesday, March 17 2020

Authors :

By Robert Auers and John Auers

The dramatic events of the last week and a half have thrown the entire world and each of our individual lives into very unpredictable and scary territory. This is certainly true for the petroleum industry as well, which has seen oil prices, product demand (both actual and expected), and company market values driven down steeply. This brings to mind the title and lyrics of Tom Petty’s 1989 classic opening track, “Free Fallin’ ” from his debut solo album, “Full Moon Fever,” (which in this case could be retitled “COVID Fever). It is impossible to predict what comes next, in regards to either the COVID-19 pandemic or the oil price wars, but we do know that that there is some limit to how far things can fall. The key questions are: what that limit is and how quickly can prices, product demand and valuations bounce back. In an effort to analyze what the possible answers to these questions could be, we’ve looked back at how oil markets responded to previous shocks to the system over the past 30+ years. Of course, the current situation is unprecedented and every one of the previous events we reviewed was also unique, and the industry itself and the environment it operates in has changed and evolved significantly over the years. Mark Twain perhaps said it best in a quote commonly attributed to him – “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” In that light, we will focus on what we can learn from these previous events (and what might be different) in the way the refining industry is impacted by the combination of the COVID-19 demand and Saudi/Russia conflict supply shocks.

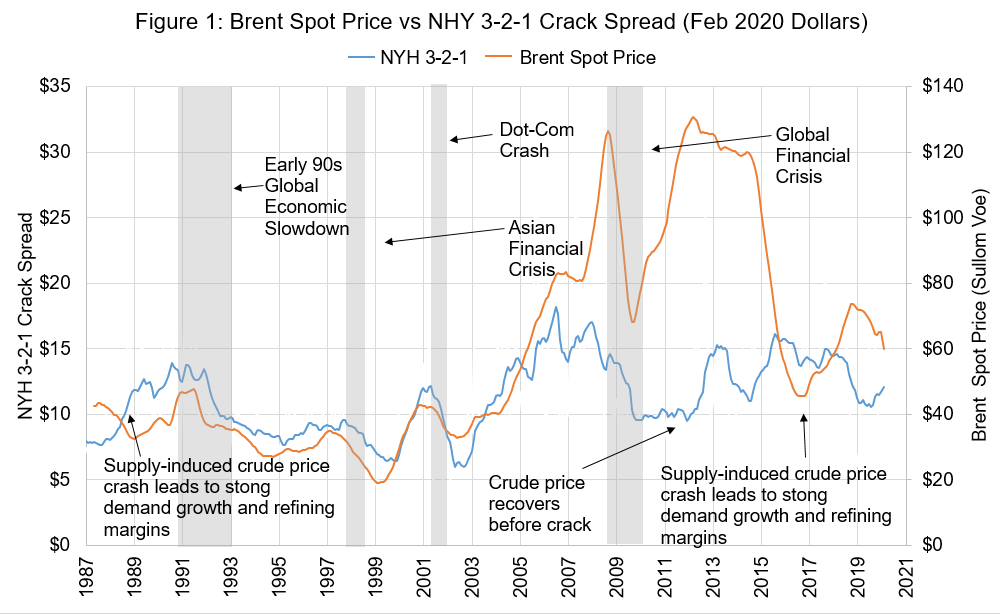

People typically associate low crude prices with low refining margins, but this is not always the case. In fact, we believe the direct effect of crude prices on refining margins is small. The more important factor is the driver of the low/high crude prices. If crude prices fall due to declining global petroleum demand growth (or outright demand declines), refining margins will naturally suffer, as refining capacity is constant in the short term. We witnessed this situation during the 2008-2009 financial crisis; however, if the price decline is the result of surging supply growth (as we saw during the 2014-2016 price crash), the resultant strong demand growth will likely lead to strong refining margins – at least until new capacity additions can be added. Figure 1 shows the historical Brent spot price on the right axis and the New York Harbor (NYH) 3-2-1 crack spread on the left axis. Recessions and periods of slow global economic growth are highlighted in gray.

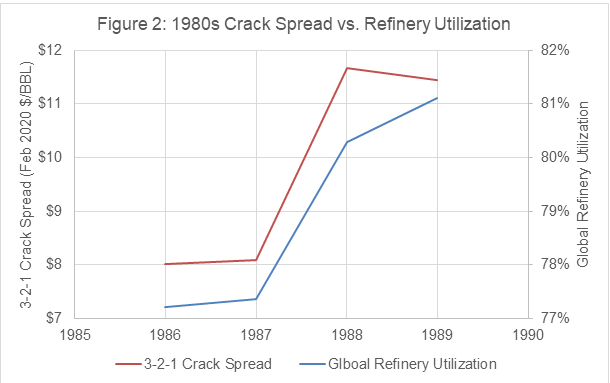

In Figure 1, we have noted two supply-induced crude price crashes that led to strong refining margins – 1986-1988 and 2014-2016. From August 1985 through the summer of 1986, OPEC increased crude oil production by ~4 MMBPD, causing the WTI spot price to fall from nearly $30/bbl in mid-1985 to a low of around $12.6/bbl in March of 1986. As a result, global petroleum demand growth increased from annual average just 507 MBPD for the 1982-1985 period to 1.7 MMBPD for the 1985-1988 period. Nonetheless, as a result of a long period of slow global demand growth prior to 1986, global refinery utilization rates were low (average of 74.6% in 1985) heading into the price crash, and it took until 1988 for global demand growth to trigger refinery utilization rates high enough to increase global refining margins. Figure 2 displays global refinery utilization vs. the NYH 3-2-1 crack spread for 1986-1989.

During the second major supply induced price crash shown in Figure 1 (2014-2016), global refinery utilization in 2014 was already at 80.1%, prior to crude price collapse. This meant that very little delay existed between the price collapse and increased refining margins, with NYH 3-2-1 crack spread increasing from $12.94 in 2014 to $15.71 in 2015. Refining margins then fell considerably beginning in the fourth quarter of 2018 and have remained below the average level seen during the 2015-2017 time period due primarily to slowing global demand growth, which, in turn, resulted from high absolute crude prices in 2018 and slowing global economic growth in 2019 and 2020. An uptick in new refinery completions in 2019 further contributed to this decline in margins.

Demand-induced price declines (generally the result of global economic growth slowdowns/recessions), on the other hand, lead to both falling absolute crude prices and refining margins. Four of these periods have been highlighted in Figure 1 – the early 90s global economic slowdown, the Asian financial crisis in 1997/1998, the dot-com crash in the early 2000s, and the Great Recession in 2008/2009. Each of these events led to a nearly immediate decline in global refining margins; however, the declines after both the Asian Financial crisis and the dot-com crash were relatively short-lived, as these were relatively minor economic slowdown and petroleum demand recovered rapidly. The early 90s economic slowdown was similarly mild, but rapid recovery in refining margins did not occur once refining margin and demand growth recovered. This was largely because rapid growth in global refining capacity (particularly in Asia) prevented such an increase. The Great Recession, on the other hand, was a much more severe economic shock and this resulted in a longer period of depressed refining margins. The problem was further exacerbated by a slew of new refining project completions taking place between 2008 and 2011, as the strong margins seen during the “Golden Age” of refining from 2003-2007 triggered a wave of new investment in the industry.

So this brings us to today. The price of Brent crude had fallen significantly from its high of almost $75 per barrel back in May 2019 even before the collapse of the OPEC/Russia agreement. This was caused by both supply and demand forces, with slowing global economic growth, the loss of Chinese demand from the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan and continued increases in U.S. oil production. Prices began “Free Fallin’” on March 6 after the Russian pulled out of OPEC+ and the Saudi’s announced their plans to open their oil spigots shortly thereafter. The spreading COVID-19 pandemic and demand killing mitigation efforts have driven prices even lower, with Brent falling below $30 per barrel yesterday, hitting its lowest level since January 2016. 1Q 2020 global crude oil demand will end up with its first year-over-year (YoY) decline since the Great Recession and the 2Q numbers look to be even worse unless something changes dramatically on the pandemic front. So what does this mean for refining margins, which generally benefit from lower oil prices, but not if those are largely driven by falling demand?

Initially, international refining margins actually surged, as the drop in product prices were significantly exceeded by the rapid fall in crude prices after the Saudi announcement of price cuts and production increases; however, this follows a period of generally weak margins (caused primarily by the slowing global demand growth) seen through most of late 2019 and early 2020. U.S. refining margins, on the other hand, after a relatively weak finish to 2019 and start to 2020, did not fully participated in the spike in margins due to a simultaneous compression of the Brent-WTI and Brent-LLS differentials (due to the result of an expected decline in U.S. crude production and exports).

As time goes on, the growing impact of COVID-19 related demand effects will take hold and lead to a surplus of refined products, resulting in steeper product price drops and a fall in global refining margins. Of course, refiners will react as well, and we can expect a reduction in crude runs in an effort to adjust to the lower demand levels and limit inventory builds. The duration and magnitude of the lower margins and required run cuts will depend on how quickly the COVID-19 crisis is resolved; which, at this time, is a complete unknown, with no real historical precedent. At some point, of course, COVID-19 will be defeated. In a best case scenario, the current mitigation efforts result in the pandemic starting to come under control within the next few weeks. At that point, global refining margins could recover quickly, and be aided by the twin demand boosting effects of low crude prices and a post-lockdown rebound. Another potential positive stimulus to refining margins could come from long-expected IMO related factors, which have been delayed up to now by the other market forces. This scenario could lead to a very good environment for refiners as early as the 2H of this year. A worst case scenario is an extended COVID-19 impact period, which pushes the world economy into recession and a resulting longer-term demand decrease and low refining margins lasting into 2021 and perhaps beyond. Of course, there are a number of other scenarios (including ones which result in fundamental and long lasting changes in the global trade patterns and ways of doing business). It could be a while before we get a clear picture of how either the COVID-19 pandemic or the oil price wars are resolved and what that will mean for the prospects of the refining industry.

Turner, Mason & Company will continue to closely monitor developments related to the COVID-19 pandemic and Saudi/OPEC/Russian production negotiations and how these could impact all aspects of the oil industry. We will be commenting on our changing views on all these issues in coming blogs over the next several weeks and incorporating our updated market forecasts into our next edition of our Crude & Refined Products Outloook which will be published to clients in late July. If you would like more information on this publication or for any specific consulting engagements with which we may be able to assist, please visit our website: https://www.turnermason.com and send us a note under ‘Contact’ or give us a call at 214-754-0898. Please stay vigilant during these uncertain times and make good and informed decisions on personal interactions and hygiene practices.