The 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina’s Gulf Coast landfall arrives this weekend, so the next few days will understandably be loaded with retrospective analysis that concentrates on the human impacts caused by the storm. Historians and analysts may quibble about death totals (most reports list the number above 1400) or damages that range from $125 billion to well over $200 billion.

But as we reflect on the human and economic impacts of this tragic natural disaster, it is important to recognize how dramatically energy supply and demand has changed in those 20 years and the possible implications of those changes from major Gulf Coast hurricanes today. Simply put, the U.S. Gulf of Mexico can now be described as the world’s second most crucial chokepoint (after the Strait of Hormuz) thanks to exponential growth in U.S. exports of crude oil, petroleum products, natural gas liquids, and LNG. What happens to the USGC real estate is no longer a parochial problem—more than 40 countries are dependent on hydrocarbon molecules from Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama.

This Turner, Mason & Company (TM&C) analysis examines the dramatic changes in the USGC and Latin American infrastructure since 2005. We’ll pass the halfway point in hurricane season as the anniversary occurs, and the first half of that season did not bring any “probability cones” for possible impacts between Corpus Christi, TX, and Mobile, AL. It would be very premature to declare that “the coast is clear,” however, since the climatological peak for the storms doesn’t take place until September 10th.

Without ranking importance, here are some of the impacts on U.S. energy assets that have transformed domestic and global supply movements.

Crude Oil

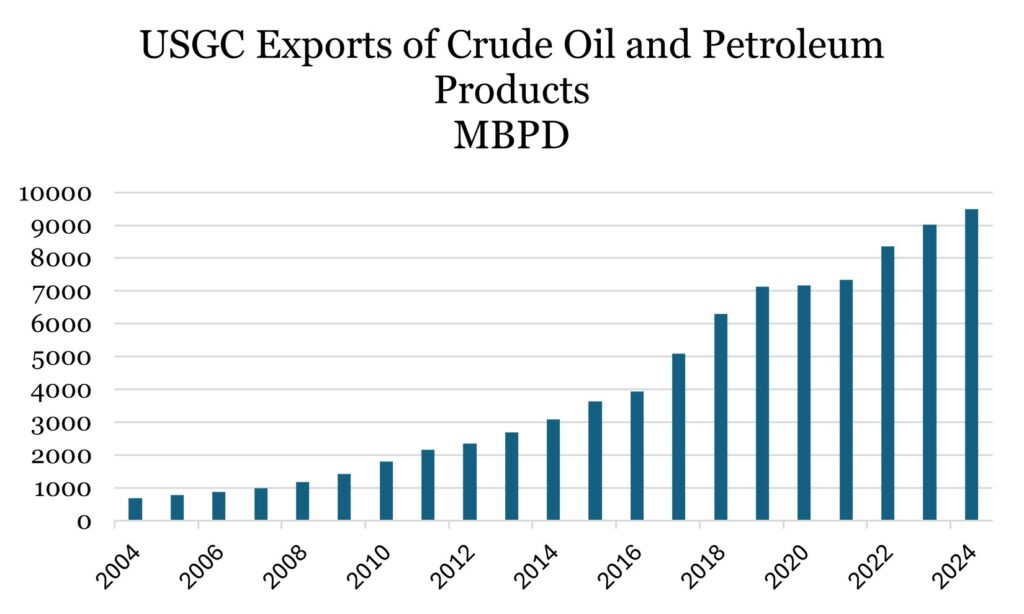

Katrina struck a decade before President Obama and Congress repealed the crude oil export ban, which had been in place since the Ford Administration in 1975. In 2025, we’ve witnessed average crude oil exports just short of 4 MMBPD (EIA 1H2025 data). That compares to a meager 17,000 PBDBPD back in August 2005. Virtually all the exports come from export terminals in Texas and Louisiana.

Most media coverage currently focuses on Permian Basin crude oil output, but considerable changes have also occurred in the Gulf of Mexico, and there will be more new oil on tap through the rest of this decade. Permian crude oil production tends to be insulated from tropical storms, but that is clearly not the case for oil fields offshore of Texas and Louisiana. However, it is noted that the Permian is indirectly exposed through midstream infrastructure constraints. If a hurricane were to force USGC export facilities offline, Gulf Coast storage would begin to fill rapidly, and shut-in risks for Permian production could emerge within three weeks.

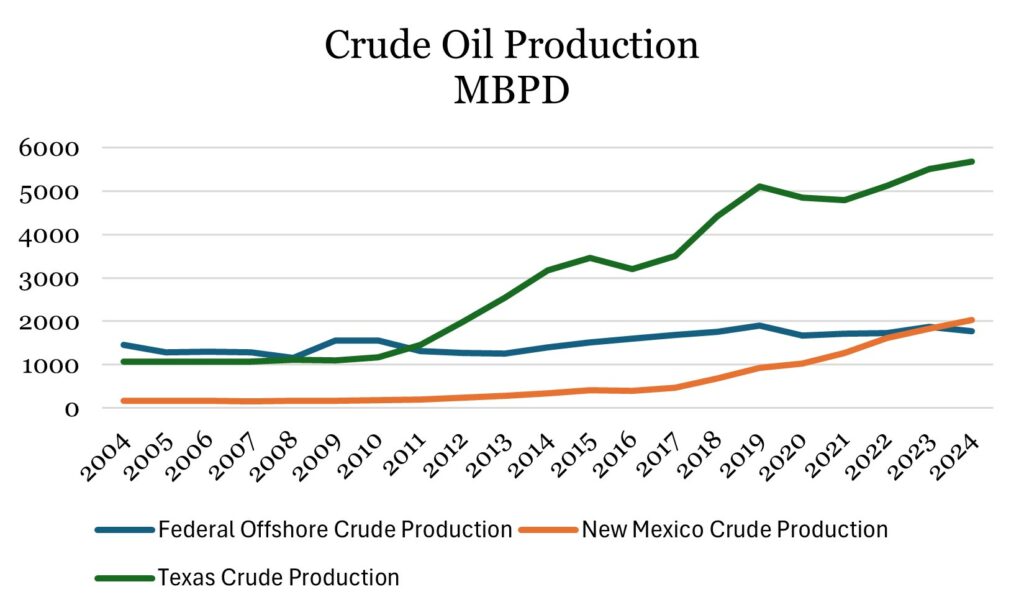

Total U.S. crude oil production was most recently estimated at 13.4 MMBPD and that compares to just 5.2 MMBPD of domestic output when Katrina came ashore. Most of the increases have occurred due to the shale revolution in Texas and New Mexico; production in these areas has risen nearly seven-fold since 2005.

But the notably weather-vulnerable Gulf of Mexico production has also climbed. A new EIA measurement will arrive on August 29, but the most recent data shows 2025 output of 1.8 MMBPD. That is up 36% from the Gulf of Mexico production number when Katrina arrived.

Note: Crude oil imports in August 2005 averaged 10.4 MMBPD or well above the most recent monthly average of 6.5 MMBPD documented in the last Petroleum Supply Monthly. The numbers add up to a 60% decline in 20 years, underscoring the importance of domestic barrels. With domestic supply now more critical, hurricane force winds and storm surge in the Gulf can have larger consequences in 2025.

Domestic Refining

Many PADD 3 refiners have raised output in the last 20 years, but we’ve lost considerable capacity as well. Lyondell shuttered its 268,000 BPD Houston refinery earlier this year, and the P66 247,000 BPD refinery in Alliance, LA was converted to a crude oil export facility following damage from Hurricane Ida in 2021.

Many of the expansions in the last 20 years are quite impressive. Nearly 250,000 BPD of new capacity was added to the ExxonMobil complex in Beaumont, TX in 2023, and smaller upgrades were seen among more than a dozen plants. Some of the increases have occurred mainly under the radar—consider that in August 2005, CITGO boasted 324,000 BPD of Lake Charles capacity and that number is now above 460,000 BPD.

Not every expansion has involved sophisticated refining equipment. Thanks to the 2015 lifting of the crude oil export ban, several entrepreneurial companies have built condensate splitters that have contributed to the U.S. fuel mix, including diesel and gasoline. Kinder Morgan, for example, can run 105,000 BPD of condensate through a facility in Galena Park, TX and Magellan (now ONEOK) has 50,000 BPD of splitter capacity at Corpus Christi.

The most chilling factoid during hurricane season may be the realization that most refinery expansions have occurred on coastal real estate vulnerable to storm surges and high winds. That said, the U.S. Gulf Coast refining system has undergone significant improvements since Hurricane Katrina, with operators investing in more resilient infrastructure, backup power, and storm-preparedness protocols. While those upgrades improve resiliency, the concentration of assets along the coast still leaves the industry exposed when major storms strike. Back in 2005, total U.S. refining capacity was 17.3 MMBPD. More recently, capacity is listed at 18.2 MMBPD nationally. PADD 3 accounted for 8.2 MMBPD when Katrina came ashore and the PADD3 number is currently just shy of 9.8 MMBPD. Most of the increases have come at the Texas and Louisiana Gulf Coasts. There is more production, but almost all of the additional capacity is threatened by tropical systems.

Latin American Refining

Sharp 20-year differences in Caribbean and South American refining might be ignored by a shallow analysis of hurricane impacts. But make no mistake about it – – the contributions of plants south of the U.S. in the western hemisphere is quite meager when compared to 2005.

There is no entity like the EIA that keeps tabs on Latin American refining, but a TM&C deep dive found some staggering differences between now and 2005.

Back in 2005, refineries in Aruba, Trinidad, Curacao, and Puerto Rico were operating and the U.S. Virgin Islands saw the St. Croix joint venture (PDVSA & Hess) run about 460,000 BPD of crude. All totaled, these plants accounted for approximately 1.3 MMBPD of processing capacity 20 years ago whereas they contribute nothing to 2025 supply.

Venezuela’s state-run oil company PDVSA also provides a notable touchstone. Ridiculously low utilization rates were first documented in 2005, and virtually no progress has been made in restoring reasonable production over the last 20 years. The immense Paraguana refining complex in Venezuela, for example, has a nameplate capacity of approximately 955,000 BPD, but operators have struggled to operate at just 10–17% of capacity in recent months. Adding to the decline, the Curacao refinery, long a key outlet for PDVSA, was shuttered in 2019.

Export Nation

Domestic demand for U.S. gasoline clearly peaked in 2016-2019 at numbers close to 9.3 MMBPD. EIA numbers imply that domestic distillate demand peaked at about 4.1 MMBPD in 2005, compared with about 3.8 MMBPD in 2024. Analysts stress that when renewable diesel and biodiesel are added to the demand mix, consumption is flat or even slightly higher than it was 20 years ago.

But the game-changer for all refined products is the unquenchable thirst for transportation fuels from Latin American countries and elsewhere. Population growth in Latin America has been brisk, but the entire region has seen no real growth in the production of refined products.

In August 2005, the U.S. exported just shy of 1.3 MMBPD of products. More recently, that number has approached 7 MMBPD. Gasoline exports, mostly from Gulf Coast refiners, total around five times the export levels seen in August 2005. About eight times as much distillate is moving from U.S. refiners to foreign destinations. And if one wanders into the NGL arena, you’ll find exports of propane almost 44 times as high as what was recorded in 2005.

Residual fuel is an outlier. U.S. companies are exporting less heavy oil than they did back in 2005 as the overall market for No. 6 oil continues to shrink.

Potential Consequences and Conclusions

All the background begs the question as to what might happen if a major storm arrives in the vicinity of refining complexes along the U.S. Gulf Coast?

Some traders operate on a fanciful rule of thumb based on the category designations from the Saffir Simpson scale. That benchmark covers winds ranging from 74-110 mph for Categories 1 and 2, with Category 3 reached when winds are at 111-129 mph; Category 4 accompanied by 130-156 mph winds; and Category 5 encompassing storms that top 157 mph wind speed.

The novel trader rubric suggests that one can cube the category designation and come up with a rough estimate of a likely price spike. A Category 1 storm, for example, might inspire a move of just a penny or so but a Category 3 hurricane could potentially move markets by 27cts/gal or more.

Hurricane Katrina came ashore as a Category 3 storm. It knocked out about 1.6 MMBPD of Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama refinery production, and kept a few refiners on the sidelines into spring 2006. The subsequent arrival of Hurricane Rita on September 24, 2005 resulted in another 1.8 MMBPD of refinery output losses. The twin storms reduced PADD 3 refinery output from about 8 MMBPD in front of Katrina to just 3.5 MMBPD after Rita. Exponential moves were witnessed for gasoline and diesel at the U.S. Gulf Coast.

Again, it’s important to stress that those exponential moves occurred against a backdrop of very modest hydrocarbon exports from the region. More recently, U.S. companies are exporting about 11 MMBPD of crude, refined products and NGLs. That compares with offshore movement of just 1.3 MMBPD in August 2005.

Most observers believe that companies will move heaven and earth to ensure adequate domestic inventories in the event of refinery downtime. They believe the Trump Administration stands at the ready with potential waivers on RVP and sulfur should a storm have the potential to disrupt supply. Draconian measures to emphasize domestic supply and perhaps limit exports are a possibility given the Administration’s ‘America First’ efforts. Still, it is worth noting that crude and distillate stocks are currently at the bottom of the five-year range, while gasoline inventories are also trending lower, leaving a significantly smaller buffer should disruptions occur.

It’s also worth noting that the current odds favor no storm impacts that will compromise supply. Various measurements of the odds of a major storm hitting the Texas Gulf Coast are around 19%, while Louisiana garners an 18% probability. A basic axiom through the years holds that all hurricanes coming ashore on the Lower 48 states diminish demand, but it is only the rare tempest that impacts supply.

However, it’s wise to be aware of the dynamic and relatively little-discussed changes that have occurred in the last 20 years. The U.S. Gulf of Mexico isn’t often recognized as a global “choke point” for oil and other hydrocarbons. However, in many respects, the region is more vulnerable to storm impacts than it was when Katrina made landfall on August 29, 2005. That’s a sobering statement as the country approaches the halfway point of the 2025 hurricane season this weekend.